The New WNBA CBA: Perspectives from Management

In the world of labor negotiations, management often assumes the role of the “tough guy” or “villain.” However, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver and WNBA Commissioner Cathy Engelbert, along with league owners, seek to redefine the current WNBA collective bargaining process, highlighting common interests: the continued growth of the league and the prosperity of the players. Despite this, the players’ association has adopted a more aggressive stance, seeking public opinion and criticizing the league and its negotiation tactics. Napheesa Collier, a member of the executive committee of the Minnesota Lynx, has directed her criticism directly at Engelbert’s leadership.Recently, the WNBA has responded to some of the union’s claims, defending the management’s position. With the soaring increase in the valuations of WNBA franchises, a new television deal that will begin in 2026, and expansion to 18 teams by 2030, the league appears to be in its best financial shape since its launch in 1997.

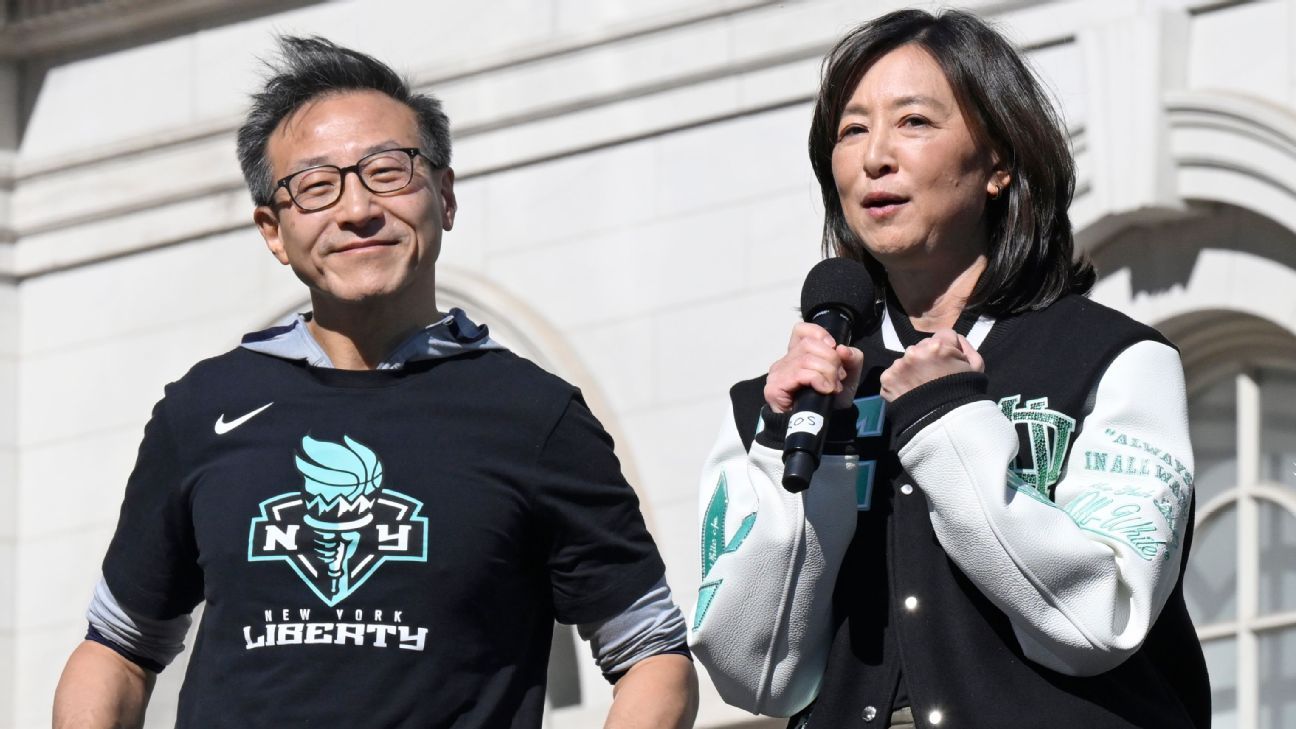

Billionaire Owners

There are two categories of owners in the WNBA: millionaires and billionaires. Within these categories, there is a notable difference in their willingness to spend. Joe Tsai, owner of the New York Liberty along with his wife Clara Wu Tsai, has always been willing to provide what he considers necessary to turn the Liberty into a world-class franchise. Joe Lacob (Golden State Valkyries), Mark Davis (Las Vegas Aces), and Mat Ishbia (Phoenix) are in the same category: owners willing to invest money to obtain greater benefits. They are the owners who also own NBA teams or other professional sports, whose WNBA teams play in NBA arenas or larger scale and have state-of-the-art facilities. Regarding the CBA, they might be willing to agree to give the players a larger share of the revenue because they are confident in the money they will continue to earn from attendance, jersey sales, and other sources of income. A source told Alofoke Deportes that these owners really see the WNBA, like the other teams they own, as an investment business. As long as the product continues to generate money, the owners will invest in it at higher levels.

Independent Owners

These owners helped keep the WNBA afloat when NBA owners lost interest after the league’s first few years. A group of season ticket holders kept the Storm in Seattle when the NBA’s SuperSonics moved to Oklahoma City. The Mohegan tribe was the WNBA’s first independent operator, moving the Orlando Miracle to Connecticut in 2003.

Once a key voting bloc, independent owners are now in a clear minority, as NBA owners have seen the renewed financial potential of women’s basketball. Even the possible sale of the Sun has been complicated by the WNBA’s desire to prioritize bidders from the league’s most recent expansion round, which awarded the three teams (Cleveland, Detroit, and Philadelphia) to NBA groups. Given their more limited resources, independent owners are understandably more focused on limiting expenses and maintaining a level playing field. They also have the strongest argument for recouping the losses they have incurred in operating their franchises when the WNBA’s revenue streams were not as strong. At the same time, that shouldn’t be confused with a lack of investment. The Storm used a capital raise to build the league’s second WNBA-specific practice facility, which opened in 2024 and remains state-of-the-art.

Expansion Teams:

After the Valkyries had a historically successful debut season for an expansion team, there are five more newcomers waiting in the wings. Just a few years ago, Mark Davis paid only $2 million to buy the Aces franchise; new parties have paid exponentially more to get on the WNBA’s growth train. The most recent expansion fee for the Detroit, Cleveland, and Philadelphia franchises, whose ownership groups also own NBA teams in those respective cities, was $250 million, not including investment in practice facilities. The expansion teams most eagerly awaiting a new CBA are the Portland Fire and the Toronto Tempo, who will have their inaugural seasons in 2026. The rules for the upcoming two-team expansion draft must be collectively bargained, so those franchises won’t be able to build their rosters until a new agreement arrives.

General Managers

Although general managers are not directly represented at the table, the rules established in the CBA help regulate the construction of the roster, as well as the financial division between owners and players. In particular, executives, who are much more important than in 2020, as the general manager position has become a full-time job instead of a role also performed by the head coach, will be watching to see how much more flexibility the new CBA might grant them.In a way, the WNBA’s strict salary cap has actually forced more difficult decisions than in the NBA, where teams can spend beyond the cap to retain their players. On the other hand, however, there are no exceptions to use, and the strict salary cap in the WNBA can make it difficult to make mid-season trades. Deals have become increasingly common in recent years, but there is no comparison to the NBA’s high-profile trades that generate excitement for the playoffs.

Limiting the number of protected salaries per team is a restriction that seems to have outlived its usefulness. For the short term, general managers also need to know how the WNBA will handle the upcoming expansion drafts, starting with Portland and Toronto this season. With almost all league veterans becoming unrestricted free agents, allowing teams to protect six players, as was the rule for last year’s Golden State expansion draft, could leave Fire and Tempo with few good options.