The Pacers: Masters of Comebacks in the 2025 NBA Playoffs

The 2025 NBA playoffs have been marked by a series of epic comebacks, but the Indiana Pacers, champions of the Eastern Conference, seem to have mastered this art perfectly. Their ability to overcome adverse situations has been key on their path to glory.

In the first round against the Milwaukee Bucks, the Pacers overcame a seven-point deficit in the final 40 seconds of overtime to secure the series victory (4-1). In the Eastern Conference Semifinals, they repeated the feat in the final 50 seconds of the second game against the Cleveland Cavaliers.

But his most stunning performance came in the first game of the Eastern Conference Finals. After being 14 points down with four minutes left in regulation and eight points behind in the last minute, the Pacers, thanks to Aaron Nesmith’s three-pointers, errors by the New York Knicks and a buzzer-beater by Tyrese Haliburton, forced overtime and took the initial victory of the series.

Inspired by Indiana’s comebacks and the fact that the Knicks won three games they were losing by at least 20 points, the most for a team in a single playoff run in the play-by-play era (starting with the 1998 playoffs), let’s analyze how comebacks have dominated the 2025 playoffs.Are the Pacers the best comeback team in NBA playoff history?

The short answer, limiting ourselves to the period in which we can quantify comebacks, is almost certainly yes. The long answer, which involves quantifying this title, is complicated.

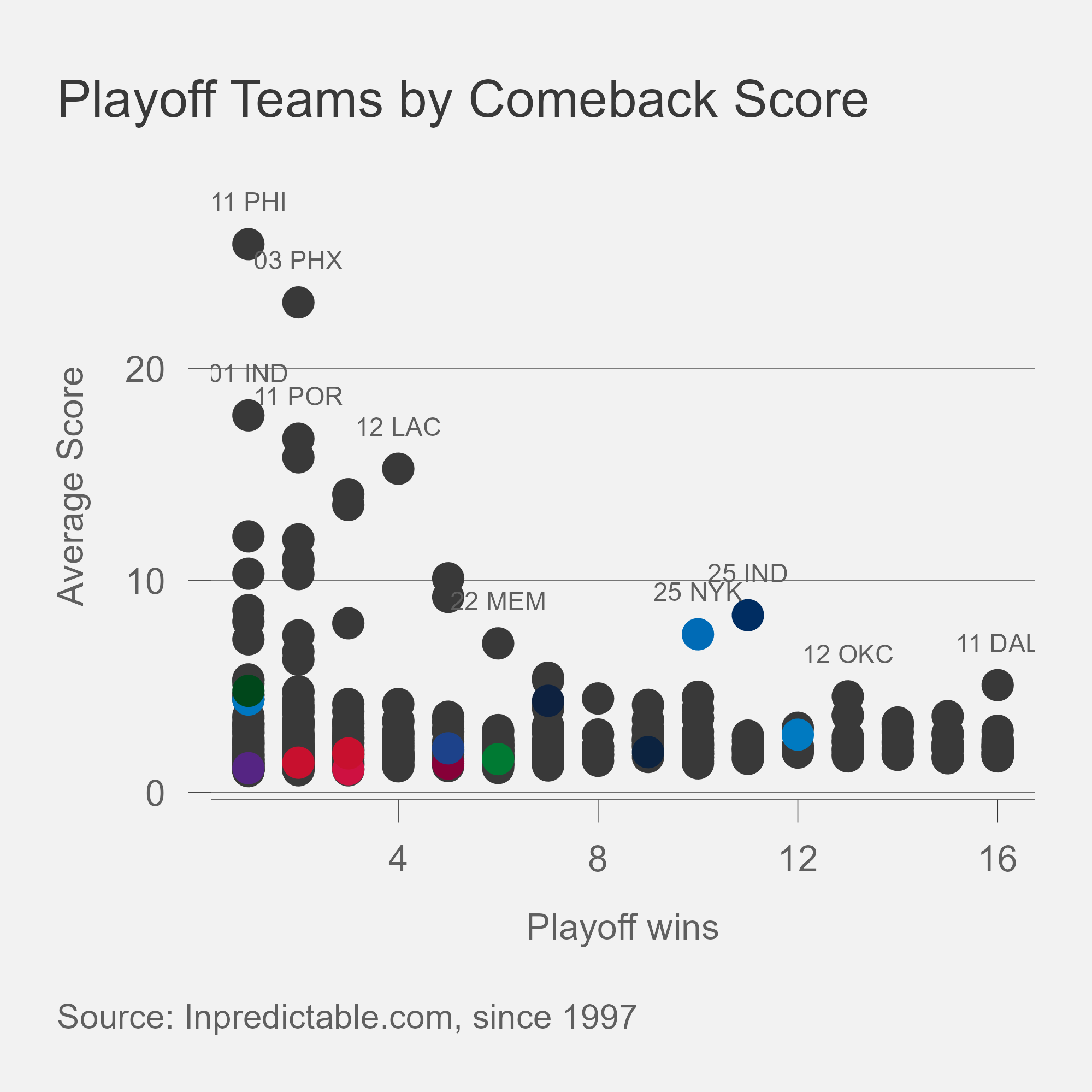

Mike Beuoy from Inpredictable.com, a valuable resource for the NBA, has delved into the topic of win probability and comebacks. This website evaluates each game with a comeback score based on the winning team’s lowest point probability, and Indiana’s three long-distance victories are among the top seven comebacks in the playoffs since 1997.Inpredictable also analyzes the average comeback score for each of a team’s wins. Technically, it’s the geometric mean, which weights an atypical comeback with less weight than the traditional mean. Despite this adjustment, it’s still easier to build a high comeback score with fewer comebacks than the Pacers (and the Knicks) have achieved so far. By graphing the average comeback score for each playoff team since 1997 against their wins, with this year’s teams highlighted by primary color, it’s obvious how atypical Indiana and New York are.

Working with Beuoy, we tried a few different methods to find a unique comeback method that takes into account both the volume of comebacks and their improbability. The most satisfying one we found was to take the product of the probability of each win at its lowest point, i.e., the odds of a team winning all the games they won in the playoffs.

By analyzing things this way, teams with more playoff wins are greatly favored, whether by comebacks or not, as no game has a 100% chance of winning from the start. Nevertheless, the Pacers’ 12 wins (and counting) rank second since 1997 in this group, behind only the 2011 champion Dallas Mavericks, who had 16 wins. You can see Dallas in the table as the one with the highest comeback score of any title winner.

Meanwhile, the Knicks’ 10 wins are in seventh place, higher than any team before this year without reaching the Finals.

Are Win Probability Models Underestimating Comeback Chances?

Indiana’s three comebacks have seen the team victorious after win probability estimates gave them a 2.1% or less chance of occurring, including 0.9% against New York. It’s not like being struck by lightning twice (the odds of that happening once are estimated at .000065%, based on an 80-year lifespan), but it’s highly improbable by pure chance.

Based on that, some skepticism about the probability of winning can be forgiven. Part of the challenge is that these estimates are based on historical data that may not always keep up with the fast-paced NBA. ESPN’s model, for example, was built in 2017 based on training data from the last seven seasons. As comebacks become more common due to a faster pace of play and a higher volume of three-pointers, a trend I wrote about with Baxter Holmes of ESPN in 2019, we may be underestimating the possibilities to some extent.

The other problem is calibration. All models have uncertainty, but the difference between a 57% probability of victory and 58% is irrelevant in most practical contexts. At the extremes, uncertainty is magnified because a comeback from a 98% probability of victory is twice as likely as one from 99%. And a 99% comeback (one in 100 possibilities) is 10 times more likely than a 99.9% comeback (one in 1,000).Therefore, even small calibration issues are important. Is there a statistic that quantifies the good functioning of the Pacers’ offense and defense with each other?

There could be an explanation for why this particular postseason has seen so many comebacks, when most of the factors cited have been in place for years: the relationship between offense and defense. Offenses are usually somewhat more effective after getting a stop because it allows more opportunities for early offense and counterattacks on defense, but the benefit of getting a stop (or vice versa) can depend on a variety of factors that change from team to team and from season to season.

In general, these playoffs have presented a huge difference in efficiency depending on whether the offense starts with a defensive rebound or brings the ball out of bounds after a made basket. Going back to Inpredictable.com, their data shows that teams average 1.17 points per possession after a defensive rebound compared to 1.07 after a made shot or a live ball turnover. (The average for steals, or live ball turnovers, is much higher at 1.23 points per possession). That’s a change from the last playoffs, when the difference by type of start has been much smaller: only 0.01 points per possession better in 2022 and 2023.

As for why that might have changed, I would point to the increase in physicality allowed by the referees in the playoffs over the last two years. Inevitably, physicality is a bigger problem during half-court situations rather than transition. During the 2023 playoffs, when whistles were stricter, teams averaged 1.1 points per possession after a made shot or dead-ball turnover.

I think that might be related to why avoiding turnovers has been crucial in this year’s playoffs. As Owen Phillips of F5 Newsletter has been tracking, the team with fewer turnovers has gone 53-20 (.726), which would be the highest winning percentage for those teams in a single recorded playoffs. Last year, the teams with fewer turnovers won only 60% of the time, about the average of the last decade (62%). The winners of the turnover battle barely exceeded .500 in 2018-19 (41-37).

It’s more difficult to explain why teams are scoring so efficiently after defensive rebounds this year, although fatigue could be a factor with starters from several teams that reached the conference semifinals logging a lot of minutes.

Shifting our focus to Indiana specifically, the Pacers derive more benefits than most teams from defensive rebounds. They have averaged 1.26 points per possession after that, according to Inpredictable, the third-best in the NBA. Although Indiana is still third after a made shot or dead ball turnover, their efficiency drops by .16 points per possession above average.

On the other end of the court, we see a similarly large split. The Pacers’ defense is the 10th best after a made shot or dead ball turnover and .17 points per possession worse after a defensive rebound, falling to 14th.

Now, what does this have to do with comebacks? The greater the difference between stops and scores at the other end of the court, the more likely a team (or a league) is to be more irregular because the magnitude of each possession is amplified. A stop not only prevents the opponent from scoring, but also boosts the team’s offense, and vice versa: a virtuous or vicious circle, depending on your perspective.

The more irregular the game, the more likely teams are to build large leads and the more likely opponents are to come back from them. Add it up and you have the recipe for Indiana’s comebacks.

On the other hand, despite losing a lead in the final quarter in the first game of their series with the Denver Nuggets and staging a comeback from 26 points down at halftime against the Memphis Grizzlies, the Oklahoma City Thunder haven’t relied so much on their offense to be successful defensively. Oklahoma City has been very good at defending after a made shot or a dead ball turnover (second per possession after the Detroit Pistons), but is allowing .08 points per possession less than any other team in possessions that begin with defensive rebounds.