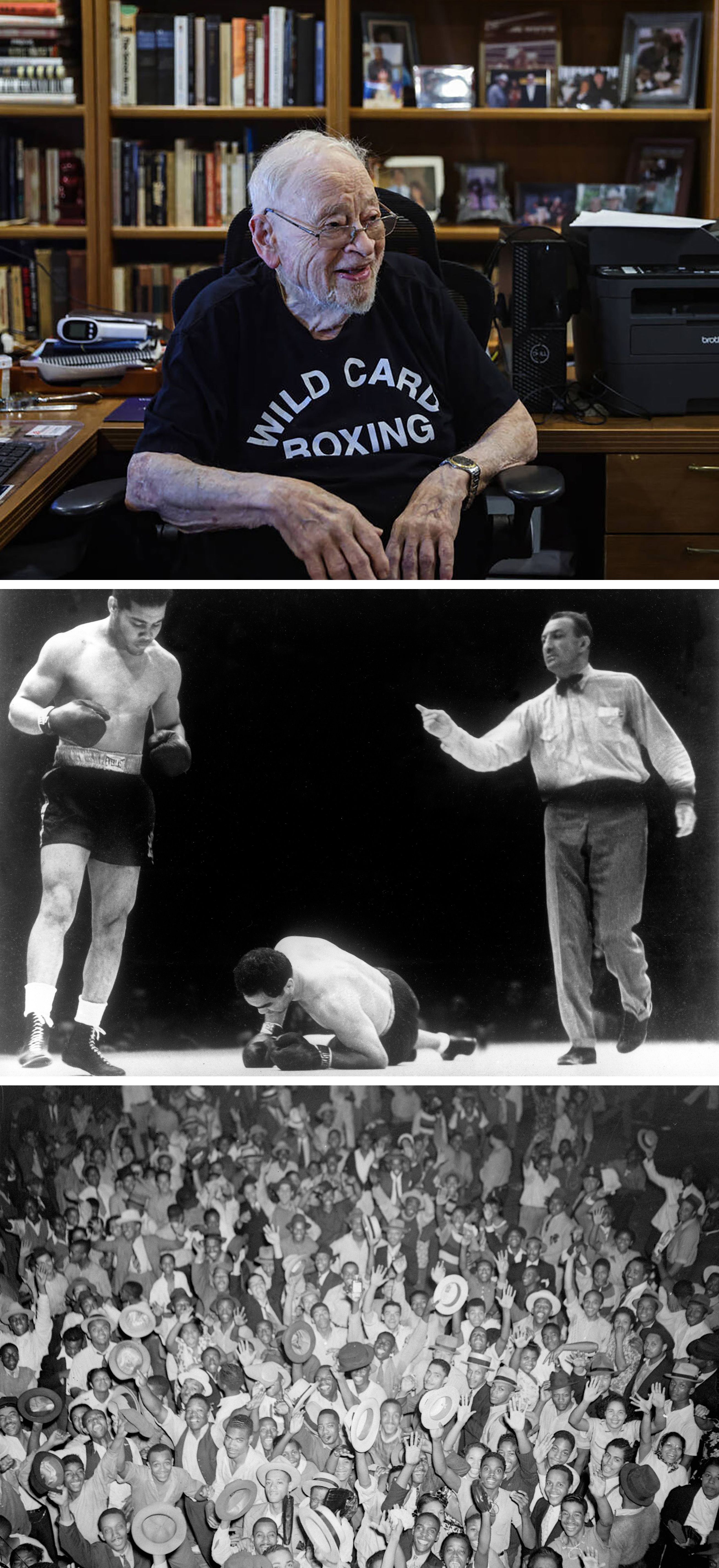

Carl Washington: The Architect Behind Crawford’s Dream

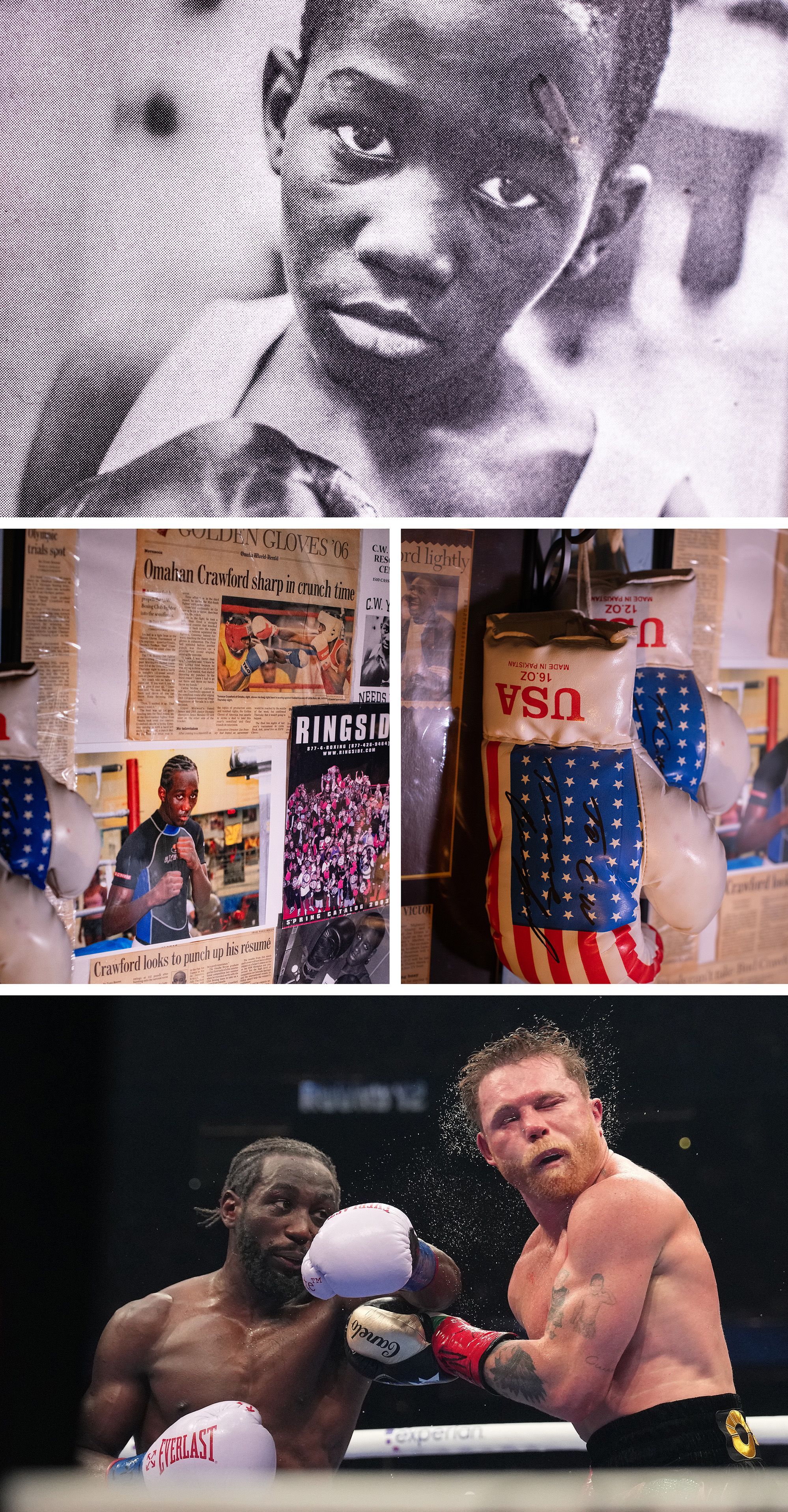

“I am the one who pushed him to look for Canelo,” says Carl Washington, about three months before the most important fight of the year. A battle that could be the last of its kind. He speaks of Terence Crawford, whom he calls Bud. Washington is especially excited, as it is the kind of fight that Crawford has sought for years. A way to prove his greatness. And against whom better than against the current face of the sport: Saúl “Canelo” Álvarez? If anyone knows what Crawford needed to fight, it’s Washington. He runs a boxing gym in downtown Omaha. The same one who, almost 30 years ago, asked a school-aged boy living in the back house if he wanted to box. That was Bud.While Washington talks, young boxers slowly fill their gym, the CW Boxing Club, for another day of training. Some are professionals, but most are amateurs. They all dream of becoming world boxing champions, and they all agree that being from Nebraska makes it easier to be overlooked. “How was Crawford as a young boxer?”, I asked. “Bud was a wicked boy,” says Washington. It tells the story of the first time Crawford got into the ring and became so enraged and frustrated by the blows that tears of rage flooded his eyes. He took off his gloves, wanting to fight bare-knuckled against his opponent. “Bud just started hitting him, he didn’t want to stop,” Washington recalls. “It happened in that corner over there,” he says as he points to a ring where the boxers have begun to warm up. “I told everyone I was going to be world champion,” says Washington. Crawford, who has his own gym in North Omaha, stopped training here a while ago, but the CW Boxing Club is where it all began. Where, for a long time, few outside of Omaha knew his name. Back then, managers and promoters told Crawford that if he wanted the best for his career, he would have to leave this place. Not only did he stay, but he surrounded himself mainly with people who also started here. And for years, they all waited for a fight like this. For most of Crawford’s career, boxing politics kept him away from the big fights. He was caught between the cold wars that promoters have with each other. Crawford’s unique talent was evident; a fighter with supreme intelligence who was also athletic enough to switch from orthodox to southpaw in the middle of rounds. But without opportunities to fight the best, it was difficult to prove how special he really was. In the fight against Canelo, he finally had the opportunity, at 37 years old, to participate in the kind of fight he had been waiting for. He had won titles as a super lightweight and welterweight, but this was a superfight, a battle between athletes that, even before it began, felt like a battle between legends. “Let me show you something,” Washington says to me. I follow him as he walks through a maze of walls that, like everything in his gym, he has built with his own hands. He turns a corner, takes a few steps, and then stops to look at something else he has built. “I call this his historical wall,” says Washington, looking at what appears to be a secular shrine for Crawford, the boxer who came out of here. They are photographs and newspaper clippings from when he was an amateur and a young professional. It includes a framed sheet of paper that is labeled “Team Crawford.” Below are small portrait photos of nine men with Crawford at the top. Each is accompanied by a single sentence explaining how many years they were also at the CW Boxing Gym. Washington built it to show everyone what is possible. Crawford’s oldest photo is from when he was just a boy learning to box. Young Crawford is standing in a fighter’s pose, with his right hand ready to strike while his left is ready to attack. He is wearing a white tank top that is almost falling off his left shoulder and boxing gloves that are too big for his hands. His eyes look innocent and intense. Washington has two copies of that photo. One hangs in the gym he has run for almost half a century. The other copy is kept inside the Washington family Bible. It is the King James version, the cover is black and worn from daily reading. Although no one in the family knows exactly when they got it, they know it is older than the photograph it protects. “I always knew I would be world champion,” Washington says again.“I told him: ‘Do you know what your dream fight would be?’” Washington continued. “’Canelo. Then you and your grandchildren can retire.’”

Carl Washington

Canelo Álvarez: The Face of Boxing in the Spotlight

““Can we turn off the air conditioning?”, asks Canelo in Spanish. She stands in the middle of a boxing ring at the UFC GYM in Reno, Nevada, staring at a vent that blows cold air through her red hair. She has phrased it as a polite question, but everyone knows it’s more of a demand. Three weeks until fight night. The most important fight of the year. The most watched fight of her career. During the last dozen years, Canelo has been the face of boxing. Grown from a teenager marketed as the next great Mexican fighter to a global brand, his name sells everything from tacos to luxury menswear. His business manager, Richard Schaefer, is sure that Canelo will soon be a billionaire. “Thank you,” Canelo says to no one in particular when he feels the air conditioning turn off. “This ring is smaller,” says Eddy Reynoso, his trainer. “Yes,” Canelo responds as he begins to warm up. Just as he can’t risk catching a cold, he can’t risk suffering a muscle strain. If his fight against Crawford —called everything from the “Fight of the Century” to “Once in a Lifetime”— is postponed, it will jeopardize hundreds of millions of dollars. He will risk one of the few fights Canelo has left. “They just put it up,” Canelo says about the ring. It’s located above the space generally reserved for group classes, inside the gym that is closed to its members because Canelo is here. “We apologize for the inconvenience,” reads a paper taped to the gym’s glass door. When Canelo starts skipping rope, the approximately 40 people in the gym watch. When he moves from one corner of the ring to the other, everyone’s eyes and cameras follow him. The same happens when he moves to the heavy bag and when he finishes and returns to the locker room with a sweat-stained shirt. “I’ll be right back,” he says. “I’m just going to change into a clean shirt.” Canelo has reached a level of fame impossible to escape. That’s why he uses a single name. It’s also why for the last two years he has moved his training camp an hour from here, in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The elevation helps his lungs, but more importantly, the isolation eliminates some distractions that come from being the sun in the center of the sometimes treacherous boxing universe. Canelo’s Mexican heritage plays an important role in that. The stereotype of “boxing is dead” has always been wrong. It’s more that, in this country, boxing has largely become a Latino sport, primarily Mexican. “This will be one of the most important fights I’ve had,” Canelo tells me. He has returned from the locker room wearing a purple shirt with the “No Boxing No Life” logo that is part of his brand. “I think it will be the biggest.” Beyond that, outside the ring, it will be his most important and biggest fight because it will be broadcast to Netflix’s more than 300 million global subscribers, and if nothing else, that increases the spectacle. It will be Canelo’s most important and biggest fight because, despite the disadvantages he will face, Crawford can win. The most important and the biggest. Because as he approaches the end of his career, nothing damages Canelo as an individual, boxer, and brand, more than losing.

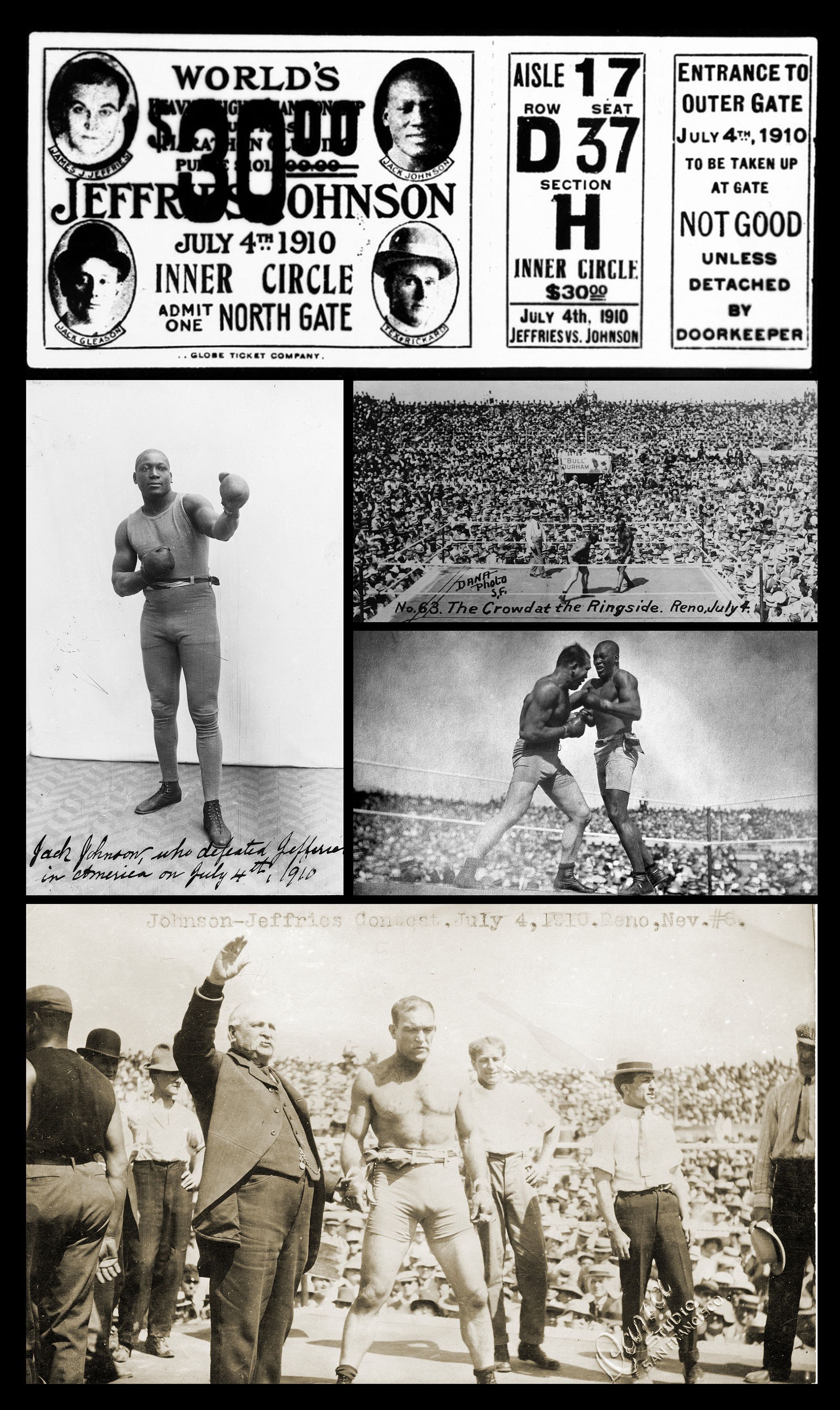

Reno: A Stage Steeped in History

There is a historical marker on E. 4th Street in Reno, about a 10-minute drive from where Canelo held his media workout. A couple of blocks north of the Truckee River, it’s surrounded by cheap motels and auto repair shops. Being there on a hot late-August afternoon is to be at the site of perhaps the most important fight in the country. On July 4, 1910, Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, faced Jim Jeffries. Their fight was filled with racial tension in a country that was still trying to find itself in the remnants of its Gilded Age, which brought immense wealth for a few and extreme poverty for many others. The fight was in Reno because the governor of California said San Francisco couldn’t host it. Boxing corrupted public morals, he argued. He was also worried about what might happen if Johnson won. If the Fight of the Century were to take place in California, he urged the attorney general to arrest anyone involved. Reno had a station on the Southern Pacific Railroad, and because the mining industry was struggling, politicians thought boxing would help Nevada’s economy. In the infancy of boxing, fights were held in secret places: in brothels and back rooms of bars, in fields in the middle of nowhere and, sometimes, on the dry banks of the rivers on the border between the United States and Mexico. All that changed with the 1897 fight between James J. Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons. Half an hour’s drive from Reno, there is also a historical marker for that fight. It is next to a leaky sprinkler box in the parking lot between the Carson City jail and the sheriff’s office. With two weeks to prepare for Johnson-Jeffries, a wooden amphitheater was quickly built. On the day of the fight, more than 20,000 people witnessed what local newspapers called The Fight of the Century. It took place at a midpoint between where the country was and where it was going. Almost six years earlier, Theodore Roosevelt won a second presidential term and further involved the country in global politics. Six years later, the United States surpassed the British Empire as the world’s largest economic power. The country was in the early stages of what would become the American Century. It embraced the optimism that came with seeing itself as exceptional and having unparalleled cultural, economic, and political power worldwide. Under the scorching Nevada sun, Johnson defeated Jeffries, leaving him a bloody mess. In the 15th round, Jeffries, the undefeated favorite who had never been knocked down, fell to the ground several times. The crowd, most of whom were there to see Jeffries win and reinstate a white man as heavyweight boxing champion, began to shout for the fight to end. When the inevitable was near, Jeffries’ corner ran into the ring to stop the beating. “No, Jack, don’t hit him anymore,” shouted Jeffries’ manager. The Fight of the Century ended, and the fans left the arena in stunned silence. A source of black pride and defiance against racial oppression, Johnson’s victory was described by the Reno Evening Gazette as “the scene of the greatest tragedy the roped ring has ever known.” Shortly after it ended, from the West Coast to the East Coast and all points in between, the country’s first national racial riot began, but that label is incorrect. It was white-on-black violence as payment for Johnson’s victory. In Walla Walla, Washington, a Black man was thrown to the ground and kicked in the head and body. In Omaha, two Black men were shot inside a pool hall after an argument about the fight. In New York, a Black man was hanged from a lamppost. And there were many others. At least 20 people died and hundreds more were injured. There was even a rumor that Johnson had been shot while traveling by train out of town. The wooden amphitheater was destroyed long ago along with most of the surrounding buildings. The last of the 20,000 people who attended the fight died decades ago. Among the last physical reminders is a plot of land with a historical marker that has been battered and bruised. It has been written on, scratched, and stained with ink. Only half of the letters are visible on what used to say “The Fight of the Century.” Today, the place that was once the center of the world’s attention is a junkyard.

The American Century and Boxing: A Deep Connection

“WE AMERICANS ARE UNHAPPY.” That was the opening sentence of Henry R. Luce’s editorial published in the February 17, 1941, edition of Life magazine. “We are not pleased with the United States. We are not pleased with ourselves in relation to the United States. We are nervous, or gloomy, or apathetic. Looking at the rest of the world, we are confused; we don’t know what to do.” With that, Luce’s 6,500-word plea to his readers began. As the co-founder of Time and Life magazines, and the founder of Fortune and Sports Illustrated magazines, he used his powerful media empire to persuade. With World War II underway and the United States not yet fully involved, Luce wanted his readers, including politicians, businessmen, and powerful industrialists, to embrace a future in which the United States would be the world power. “The 20th century is the American century,” he wrote. For that to work, Luce said, there had to be a worldwide devotion “to the great American ideals.” That meant free economic determinism and a world in which the United States was a good Samaritan, in part sharing its engineers, doctors, teachers, and even artists. It was the kind of assertion of power that included American technology, arts, and sports. The American Century. A little over seven months after Luce’s editorial, Joe Louis, the second black heavyweight boxing champion, appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Except for presidential speeches, nothing drew larger crowds to the radio than fights.

Juanito Ornelas: The Faded Dream

“WATER,” says John “Juanito” Ornelas. He’s trying to catch his breath in the stifling heat, so his voice sounds like a whisper. And since he’s wearing boxing gloves and his hands are useless except for fighting, it also sounds like he’s asking for water. Over the sounds of his own ragged breathing, Gilbert Roybal, his coach, can’t hear Ornelas. “Water,” repeats the boxer, this time louder. “The news said this is the hottest weekend of the summer,” Roybal says as he gives his wrestler a squirt from a water bottle and then unties his gloves. In any other setting, that would be great news. It’s Labor Day weekend and there are many beaches nearby. But inside the Dynamite Boxing Club, in Chula Vista, behind a bar with a payday loan and a liquor store nearby, it feels like a world away from the natural beauty of the San Diego area. Instead of the Pacific Ocean breeze, three floor fans are set to their highest speed, pointing towards the gym doors that are kept open with an orange traffic cone and a mallet with a 35-inch handle. Instead of the sweet smell of coconut and vanilla from sunscreen, the acrid smell of sweat fills the air. “We’re doing it the hard way, and we wouldn’t want it any other way,” says Roybal. He and Ornelas pride themselves on knowing they’ve earned everything they have in this cruel business. For every boxer like Canelo or Crawford who makes millions, there are thousands who work full-time just to be able to afford to fight. Ornelas fights in the shadow of hotel ballrooms and small convention halls, inside forgettable casinos in the middle of nowhere. Roybal practically has to beg sponsors for boxing gloves. They dream of fighting in a place like Las Vegas. On a night like Canelo-Crawford. “We are going to shock the world,” says Ornelas, speaking of his upcoming fight against Mohammed Alakel. It will be the first fight broadcast on Netflix as part of the Canelo-Crawford card. “I started boxing to honor my brother,” says Ornelas as he sits on the edge of the ring. “He was a professional boxer. He was 10-1-1 when he was murdered in Tijuana.”Before dying, his brother, Pablo Armenta, told Ornelas about his boxing dreams. Ornelas listened as his older brother spoke about how he studied videos of past and present world champions and dreamed of becoming one of them. About wanting to fight on the biggest stages under the dazzling lights of Las Vegas.

The Contrast of Lights: From the Forgotten Gym to the Splendor of Las Vegas

There’s a building in the part of Las Vegas where the lights don’t shine so bright and artists write on the walls. “Johnny Tocco’s Boxing Gym” the sign says, even though it’s been closed to the public for about three years. Its windows are boarded up and “Home of the world champions” written above the entrance has begun to peel off. The mural of all the famous boxers who have trained there, Sonny Liston, Marvin Hagler and Mike Tyson among them, has begun to fade. And next to the door that once opened for fighters, someone has placed a sign asking if you have sinned today.There’s another building, about a mile and a half away, in the part of Las Vegas where the beautiful people play. It’s a luxury resort and casino, the tallest habitable building on The Strip, and on top of it says “Fontainebleau”. It’s one of the newest buildings there, on top of the land that used to be the Algiers Hotel and what was first the Thunderbird, then the Silverbird, then the El Rancho Hotel and Casino. Those closed, were imploded, and after the smoke and debris cleared, Fontainebleau Las Vegas was built for $3.7 billion.

The first building is where yesterday’s boxers used to train. They are no longer there. The second is where, for at least a week, today’s boxers are seen. More at home in the first than in the second, most of them seem out of place, except for one.

Canelo at the Summit: A Spectacle Under the Las Vegas Lights

Canelo exits the suicide doors of a black Rolls-Royce that has a thin red stripe along its side. He runs his hands over his torso to straighten the white suit he wears without a shirt. He greets important people in much more conservative suits than his own. They are the money men who make the fights happen. Their names are unknown to most, but their faces loom in the background, reflected in the dark glasses Canelo wears as he thanks them. He walks towards the side entrance of the Fontainebleau Las Vegas. “¡Viva México, cab—-s!” shouts a man in Spanish from inside the south lobby of the hotel and casino hosting the Canelo-Crawford fight week. The crowd begins to cheer as Mexican flags wave from the second floor. Because he’s been the other guy during this fight promotion, Crawford received the opposite reaction when he made his entrance 50 minutes earlier. His few supporters shouting: “And the new…!” were quickly drowned out by Canelo fans. “I love all of you and each and every one of you,” Crawford said to the booing crowd, “but on Saturday, all of you are going to be crying.” He said it with a smile and the particular confidence of someone who has never lost a professional fight and is sure that he never will. “Ca-ne-lo! Ca-ne-lo!” the crowd cheers as the Mexican boxer walks the red carpet. As the week progresses towards Saturday and the weekend of Mexican Independence Day, there is growing excitement as casinos, hotels, and sidewalks will become more crowded. Among those gathered are old boxers; they are still remembered and called “Champion”. The face, the name, the logo, and the brand of Canelo are everywhere. At the airport, on t-shirts worn by those who have traveled for hours to get here, and on the largest screens that illuminate the city in the Mojave Desert. The history of boxing is the history of the search for saviors. And not for the first time, the sport seems unsure whether it wants to crown champions or put on shows. Sometimes, the most important fights are a mix of both and feel like a vacation. James J. Corbett, the champion of Irish descent, fought Bob Fitzsimmons on St. Patrick’s Day in 1897. Jim Jeffries, who was made out to be the “Great White Hope,” lost to Jack Johnson on July 4, 1910. And some of the most anticipated fights of this century, including Canelo’s fights, occurred during the Cinco de Mayo and Mexican Independence Day holidays. “Me-xi-co! Me-xi-co!” the crowd chants. Canelo walks among the flashes of cameras as hands reach out to touch him. Inside the Fontainebleau, it feels like a different world from the old building just a mile and a half away. This is where tourists come, and that is where the locals live, and they say the streets feel dead. Tourism has declined, and that has affected the local economy. The city of dazzling lights has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. Some economists warn that what is happening in Las Vegas could be an early sign of an upcoming decline across the country. Inside the Fontainebleau, which always smells of perfume and has a large crystal chandelier with thousands of crystal butterflies, that worry feels exaggerated. But standing outside the old building that has become another of boxing’s skeletons, it feels good, as if something has broken. As if Canelo vs. Crawford could be the last great fight at the end of the American Century.